Heartworm disease is a serious and potentially fatal disease in pets in the United States and many other parts of the world. It is caused by foot-long worms (heartworms) that live in the heart, lungs and associated blood vessels of affected pets, causing severe lung disease, heart failure and damage to other organs in the body. Heartworm disease affects dogs, cats and ferrets, but heartworms also live in other mammal species, including wolves, coyotes, foxes, sea lions and—in rare instances—humans. Because wild species such as foxes and coyotes live in proximity to many urban areas, they are considered important carriers of the disease.

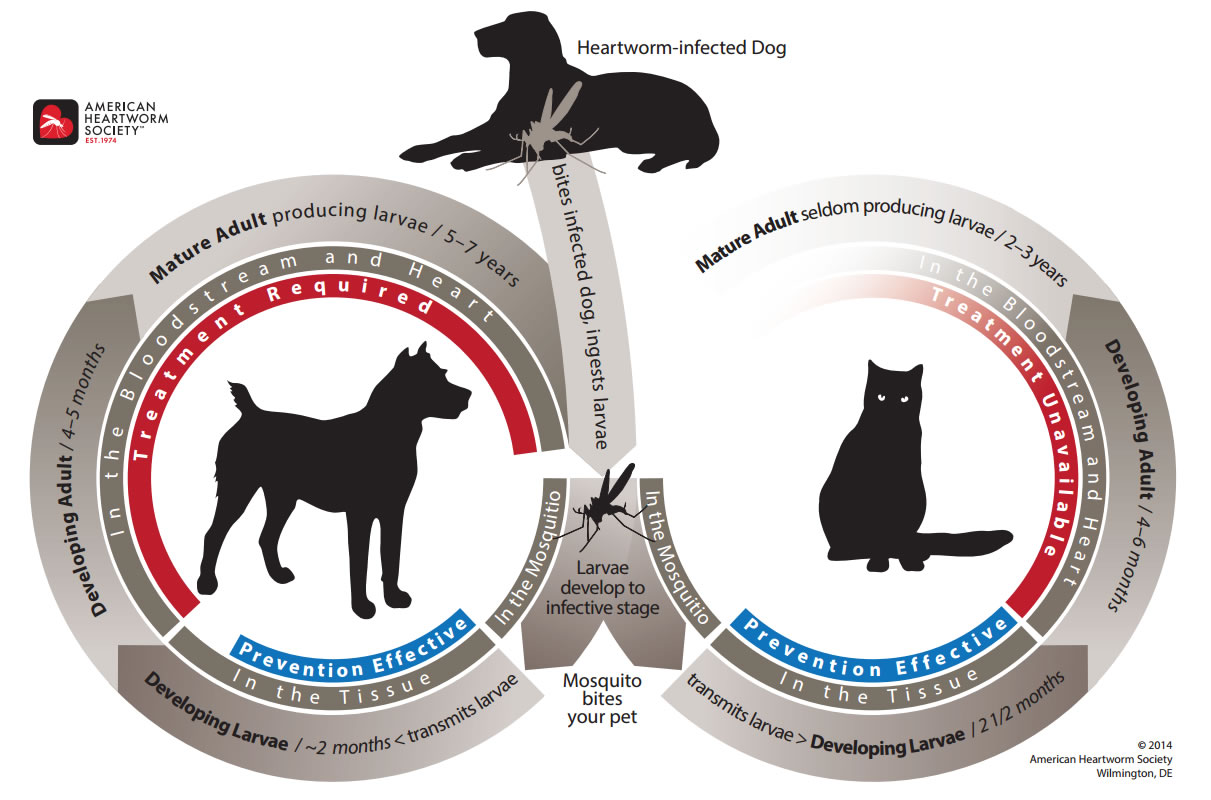

Dogs. The dog is a natural host for heartworms, which means that heartworms that live inside the dog mature into adults, mate and produce offspring. If untreated, their numbers can increase, and dogs have been known to harbor several hundred worms in their bodies. Heartworm disease causes lasting damage to the heart, lungs and arteries, and can affect the dog’s health and quality of life long after the parasites are gone. For this reason, prevention is by far the best option, and treatment—when needed—should be administered as early in the course of the disease as possible.

Cats. Heartworm disease in cats is very different from heartworm disease in dogs. The cat is an atypical host for heartworms, and most worms in cats do not survive to the adult stage. Cats with adult heartworms typically have just one to three worms, and many cats affected by heartworms have no adult worms. While this means heartworm disease often goes undiagnosed in cats, it’s important to understand that even immature worms cause real damage in the form of a condition known as heartworm associated respiratory disease (HARD). Moreover, the medication used to treat heartworm infections in dogs cannot be used in cats, so prevention is the only means of protecting cats from the effects of heartworm disease.

The mosquito plays an essential role in the heartworm life cycle. Adult female heartworms living in an infected dog, fox, coyote, or wolf produce microscopic baby worms called microfilaria that circulate in the bloodstream. When a mosquito bites and takes a blood meal from an infected animal, it picks up these baby worms, which develop and mature into “infective stage” larvae over a period of 10 to 14 days. Then, when the infected mosquito bites another dog, cat, or susceptible wild animal, the infective larvae are deposited onto the surface of the animal's skin and enter the new host through the mosquito’s bite wound. Once inside a new host, it takes approximately 6 months for the larvae to mature into adult heartworms. Once mature, heartworms can live for 5 to 7 years in dogs and up to 2 or 3 years in cats. Because of the longevity of these worms, each mosquito season can lead to an increasing number of worms in an infected pet.

In the early stages of the disease, many dogs show few symptoms or no symptoms at all. The longer the infection persists, the more likely symptoms will develop. Active dogs, dogs heavily infected with heartworms, or those with other health problems often show pronounced clinical signs.

Signs of heartworm disease may include a mild persistent cough, reluctance to exercise, fatigue after moderate activity, decreased appetite, and weight loss. As heartworm disease progresses, pets may develop heart failure and the appearance of a swollen belly due to excess fluid in the abdomen. Dogs with large numbers of heartworms can develop a sudden blockages of blood flow within the heart leading to a life-threatening form of cardiovascular collapse. This is called caval syndrome, and is marked by a sudden onset of labored breathing, pale gums, and dark bloody or coffee-colored urine. Without prompt surgical removal of the heartworm blockage, few dogs survive.

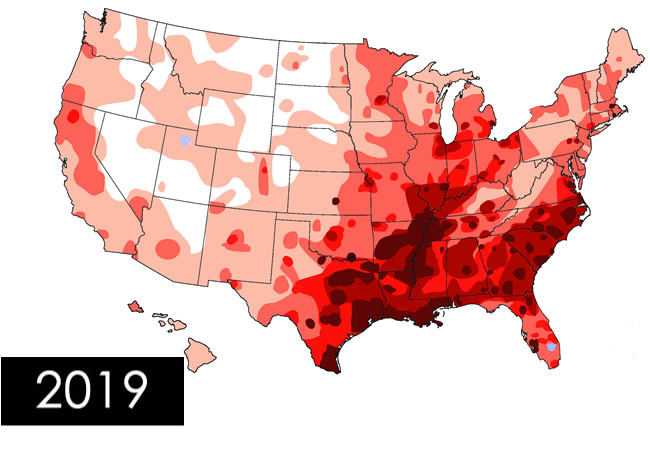

Many factors must be considered, even if heartworms do not seem to be a problem in your local area. Your community may have a greater incidence of heartworm disease than you realize—or you may unknowingly travel with your pet to an area where heartworms are more common. Heartworm disease is also spreading to new regions of the country each year. Stray and neglected dogs and certain wildlife such as coyotes, wolves, and foxes can be carriers of heartworms. Mosquitoes blown great distances by the wind and the relocation of infected pets to previously uninfected areas also contribute to the spread of heartworm disease (this happened following Hurricane Katrina when 250,000 pets, many of them infected with heartworms, were “adopted” and shipped throughout the country).

The fact is that heartworm disease has been diagnosed in all 50 states, and risk factors are impossible to predict. Multiple variables, from climate variations to the presence of wildlife carriers, cause rates of infections to vary dramatically from year to year—even within communities. And because infected mosquitoes can come inside, both outdoor and indoor pets are at risk.

For that reason, the American Heartworm Society recommends that you “think 12:” (1) get your pet tested every 12 months for heartworm and (2) give your pet heartworm preventive 12 months a year.

Heartworm disease is a serious, progressive disease. The earlier it is detected, the better the chances the pet will recover. There are few, if any, early signs of disease when a dog or cat is infected with heartworms, so detecting their presence with a heartworm test administered by a veterinarian is important. The test requires just a small blood sample from your pet, and it works by detecting the presence of heartworm proteins. Some veterinarians process heartworm tests right in their hospitals while others send the samples to a diagnostic laboratory. In either case, results are obtained quickly. If your pet tests positive, further tests may be ordered.

Testing procedures and timing differ somewhat between dogs and cats.

Dogs. All dogs should be tested annually for heartworm infection, and this can usually be done during a routine visit for preventive care. Following are guidelines on testing and timing:

Annual testing is necessary, even when dogs are on heartworm prevention year-round, to ensure that the prevention program is working. Heartworm medications are highly effective, but dogs can still become infected. If you miss just one dose of a monthly medication—or give it late—it can leave your dog unprotected. Even if you give the medication as recommended, your dog may spit out or vomit a heartworm pill—or rub off a topical medication. Heartworm preventives are highly effective, but not 100 percent effective. If you don’t get your dog test, you won’t know your dog needs treatment.

No one wants to hear that their dog has heartworm, but the good news is that most infected dogs can be successfully treated. The goal is to first stabilize your dog if he is showing signs of disease, then kill all adult and immature worms while keeping the side effects of treatment to a minimum.

Here's what you should expect if your dog tests positive:

Whether the preventive you choose is given as a pill, a spot-on topical medication or as an injection, all approved heartworm medications work by eliminating the immature (larval) stages of the heartworm parasite. This includes the infective heartworm larvae deposited by the mosquito as well as the following larval stage that develops inside the animal. Unfortunately, in as little as 51 days, immature heartworm larvae can molt into an adult stage, which cannot be effectively eliminated by preventives. Because heartworms must be eliminated before they reach this adult stage, it is extremely important that heartworm preventives be administered strictly on schedule (monthly for oral and topical products and every 6 months for the injectable). Administering prevention late can allow immature larvae to molt into the adult stage, which is poorly prevented.

The risk of puppies getting heartworm disease is equal to that of adult pets. The American Heartworm Society recommends that puppies be started on a heartworm preventive as early as the product label allows, and no later than 8 weeks of age.

The dosage of a heartworm medication is based on body weight, not age. Puppies grow rapidly in their first months of life, and the rate of growth—especially in dogs—varies widely from one breed to another. That means a young animal can gain enough weight to bump it from one dosage range to the next within a matter of weeks. Ask your veterinarian for advice about anticipating when a dosage change will be needed. If your pet is on a monthly preventive, you may want to buy just one or two doses at a time if a dosage change is anticipated (note that there is a sustained-release injectable preventive available for dogs 6 months of age or older). Also make sure to bring your pet in for every scheduled well-puppy exam, so that you stay on top of all health issues, including heartworm protection. Confirm that you are giving the right heartworm preventive dosage by having your pet weighed at every visit.

Yes. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling on heartworm preventives states that the medication is to be used by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian. This means heartworm preventives must be purchased from your veterinarian or with a prescription through a pet pharmacy Prior to prescribing a heartworm preventive, the veterinarian typically performs a heartworm test to make sure your pet doesn't already have adult heartworms, as giving preventives can lead to rare but possibly severe reactions that could be harmful or even fatal. It is not necessary to test very young puppies or kittens prior to starting preventives since it takes approximately 6 months for heartworms to develop to adulthood. If the heartworm testing is negative, prevention medication is prescribed.

Only heartworm prevention products that are tested and proven effective by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should be used.

No. At this time, there is not a commercially available vaccine for the prevention of heartworm disease in dogs or cats. However, research scientists are looking at this possibility. Right now, heartworm disease can only be prevented through the regular and appropriate use of preventive medications, which are prescribed by your veterinarian. These medications are available as a once-a-month chewable, a once-a-month topical, and a once or twice-a-year injection. You should determine the best option for your pet by talking with your veterinarian. Many of the medications have the added benefit of preventing other parasites as well.

Heartworms have been found in all 50 states, although certain areas have a higher risk of heartworm than others. Some very high-risk areas include large regions, such as near the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, and along river tributaries. Most states have "hot spots" where the heartworm infection rate is very high compared with other areas in the same state. Factors affecting the level of risk of heartworm infection include the climate (temperature, humidity), the species of mosquitoes in the area, presence of mosquito breeding areas, and presence of animal “reservoirs” (such as infected dogs, foxes or coyotes).

For a variety of reasons, even in regions of the country where winters are cold, the American Heartworm Society is now recommending a year-round prevention program. Dogs have been diagnosed with heartworms in almost every county in Minnesota, and there are differences in the duration of the mosquito season from the north of the state and the south of the state. Mosquito species are constantly changing and adapting to cold climates and some species successfully overwinter indoors as well. Year-round prevention is the safest, and is recommended. Remember too that many of these products are de-worming your pet for intestinal parasites that can pose serious health risks for humans.

Heartworm disease is very complex and can affect many vital organs, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, and liver. As a result, the outcome of infection varies greatly from patient to patient. The adult worms cause inflammation of the blood vessels and can block blood flow leading to pulmonary thrombosis (clots in the lungs) and heart failure. Remember, heartworms are “foot-long” parasites and the damage they cause can be severe. Heartworm disease can also lead to liver or kidney failure. Dogs that are exposed to a large number of infective larvae at once are at great risk of sudden death due to massive numbers of developing larvae bombarding the vascular system. Other animals may live for a long time with only a few adult heartworms and show no clinical signs unless faced with an environmental change, such as an extreme increase in temperature, or another significant health problem.

As with all drugs or pharmaceutical products, heartworm preventives should be used before the expiration date on the package, because it is impossible to predict if it will be effective or safe. The expiration date is established by a series of tests mandated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to provide assurance that the product is effective and has undergone no significant deterioration.

You need to consult your veterinarian, and immediately re-start your dog on monthly preventive—then retest your dog 6 months later. The reason for re-testing is that heartworms must be approximately 7 months old before the infection can be diagnosed.