To tailor an effective request, first consult the database's user manual. Here are 21 examples that might help.

Jan 17, 2020

In my work at The Trace , I wanted to better understand why so few shootings in America get solved. I worked with investigative reporting fellow Sean Campbell and BuzzFeed News’s data editor Jeremy Singer-Vine to request violent crime data from more than 50 police and sheriff’s departments. We used some of this data for our story, “ Shoot Someone In a Major U.S. City, and Odds Are You’ll Get Away With It ,” and posted raw data from 56 agencies online.

We also filed a request to each agency for documents that list all the fields in the databases that they use to track information on major crimes, and that explain how those databases function, such as the data dictionaries, record layouts, and user guides. We got back records from two-dozen agencies, which together cover some of the most widely used law enforcement databases in the country, extending their utility far beyond the cities we reported on (click here to jump to the full list).

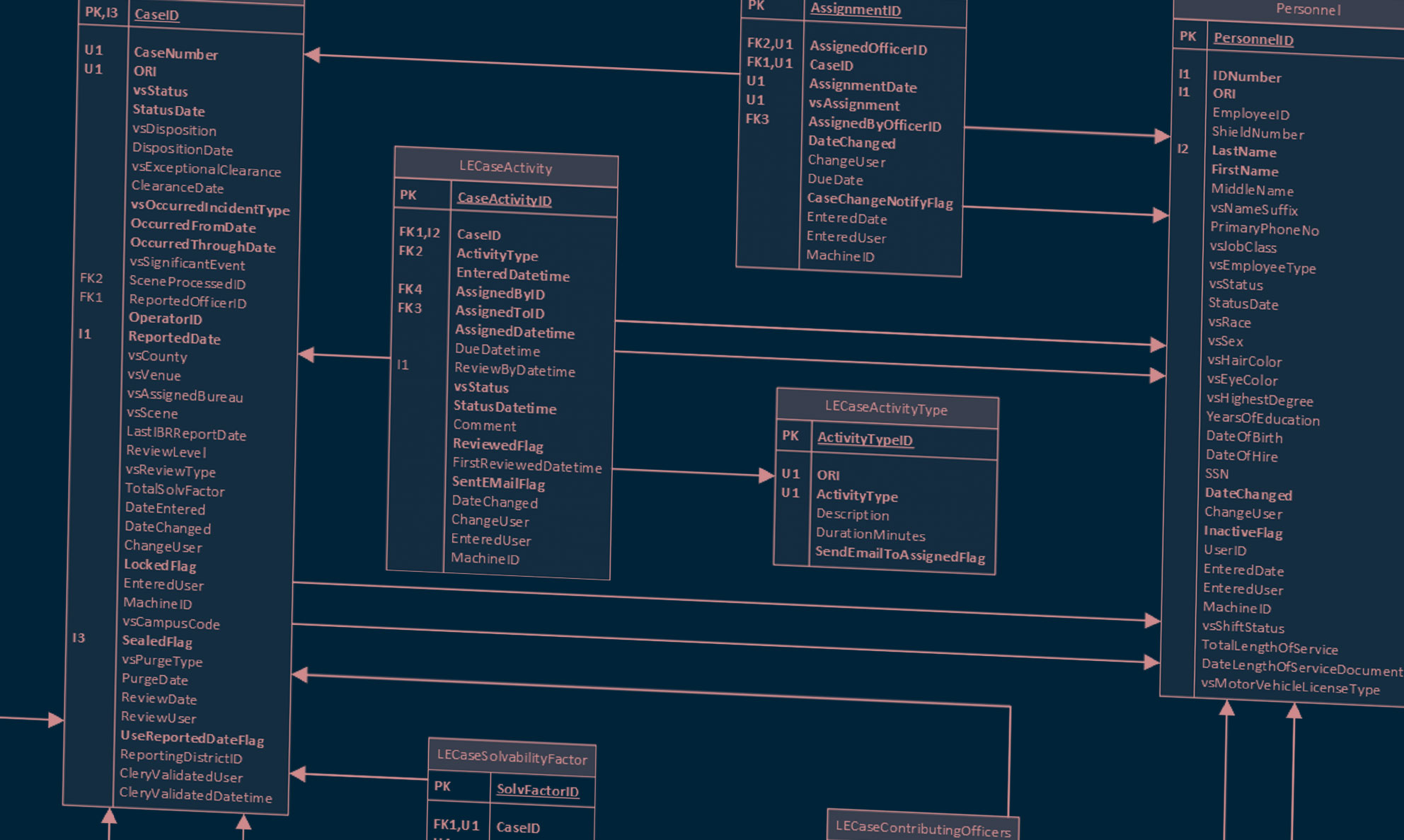

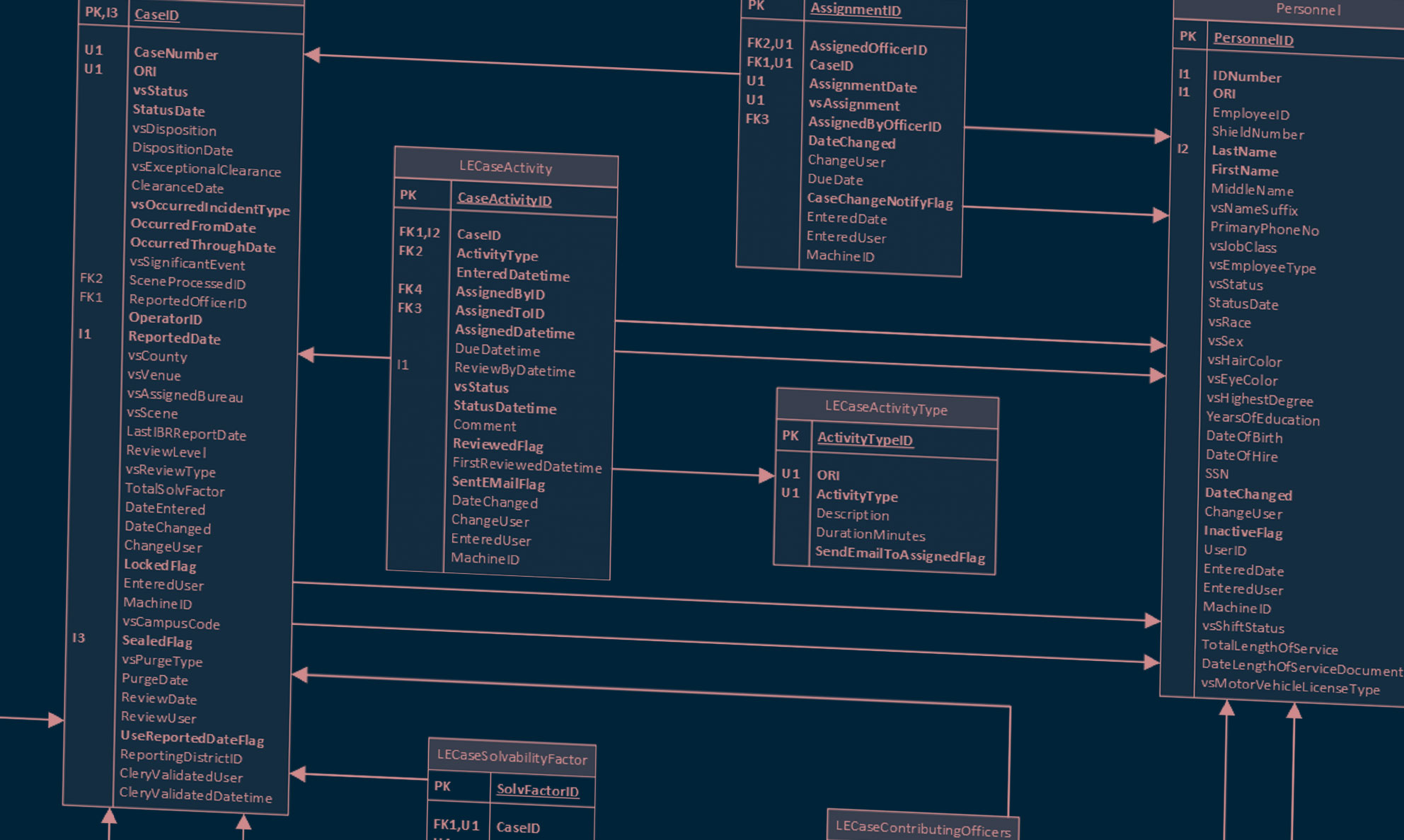

For example, the Baltimore County Police Department sent us the 2,000-page user manual for Intergraph’s inPURSUIT Records Management System, which is used to track information on practically every aspect of policing, from traffic stops to property seizures. The manual gives the name and definition of every field in the database, along with screenshots of what the officer would see during every step of the data entry process.

We’re making the data available to journalists, researchers, policymakers, and everyone else interested in examining gun violence.

In my list of data fields, I always include some version of the following:

It’s helpful to cite the provisions in the law, or court rulings, that address the most common objections to data requests.

It can be frustrating when agencies insist that they only need to release a handful of fields, regardless of what the law actually makes public, as if they are allowed to make their own rules for information that is stored as data.

In fact, public records laws often expressly state that the disclosability of information is not limited based on format. To argue this point, I’ve often attached a document that the agency has redacted that contains the same type of information I’m seeking as data. The same rules should apply. For example, the below image shows an incident report generated by the New York Police Department’s Omniform database that the agency redacted and released as a document, compared to the same report, but revealing only what’s in the crime data that the NYPD posts online. The document version gives a much clearer picture of what happened. The online data doesn’t even include a column indicating whether the crime involved a weapon.

Think of your initial request and all communication that follows as legally-binding documents. The records officer is entitled to take everything you write very literally, and if you must appeal, it could all wind up in a court file.

Once you’ve received data, make sure you got everything you requested. Frame any follow-up as missing records, not as questions. The law does not require agencies to answer questions.

“I received records on 500 homicides, yet your agency reported 600 homicides to the FBI. Please regenerate the data to include the missing 100 homicides…” is allowed.

“Why am I missing 100 homicides?” is not.

I scan my follow-up emails for question marks and rewrite those sentences as statements.

Don’t assume something has been withheld for nefarious reasons. It’s often a mistake in the query or a misunderstanding. Be friendly but firm in stating your rights.

It’s always a good idea to learn as much as you can about the database before making your request.

We obtained these documents by filing a very simple request to each agency for:

Agencies often cite security concerns or trade secrets to deny requests for the database documentation, or they simply claim the records don’t exist. To counter the first two objections, look for provisions in your open records law, or court rulings, that explicitly address database documentation, metadata, and employee manuals. To counter the argument that the records don’t exist, you could look through state regulations, contracts, and RFPs for stipulations that data dictionaries and other documentation be included with databases.

We could not have obtained data from the Newark Police Division, New York Police Department, and numerous California police and sheriff’s departments, without pro bono representation from Jean-Paul Jassy and Kevin Vick of Jassy Vick Carolan LLP; Gideon Oliver of Gideon Law; Adam Marshall and Katie Townsend of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, and C.J. Griffin of Pashman Stein Walder Hayden. Jason Schultz, director of New York University’s Technology Law & Policy Clinic, and JD candidates Suchita Mandavilli and Jake Karr, assisted with legal research.

Below are the links to the documentation that we received from various police and sheriff’s departments, and the brand of database covered by the documents. If your police or sheriff’s department uses one of these databases, you should be able to use the records in your request.

Atlanta Police Department, Georgia: In-house system

Bakersfield Police Department, California: Versaterm Versadex

Baltimore County Police Department, Maryland: Intergraph (Hexagon) inPURSUIT Records Management System, version 12.7.0

Boston Police Department, Massachusetts: Intergraph (Hexagon) inPURSUIT Records Management System, version 12.6.1

Buffalo Police Department, New York: CHARMS Globalquest

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department, North Carolina: In-House System

Flint Police Department, Michigan: New World Systems Aegis MSP Version 10.2

Indianapolis Police Department, Indianapolis: Interact

Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office, Louisiana: Automated Records and Mapping System (ARMMS)

Kansas City Police Department, Missouri: Tiburon Field Automation System version 7.4, Tiburon Records Management System version 7.4.1, and Tiburon LawRecords version 7.6

Kern County Sheriff’s Office, California: Intergraph (Hexagon) iLeads

Maricopa County, Arizona: Maricopa County Sheriff’s Department

Miami Police Department, Florida: Motorola Infotrak LRMS Version 5.3

Milwaukee Police Department, Wisconsin: Tiburon

New Orleans Police Department, Louisiana: In-House System

Phoenix Police Department, Arizona: Intergraph (Hexagon) inPURSUIT Records Management System, version 12.7.0 and inPursuit RMD Explorer version 3.0.0

Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department, California: Northrop Grumman CommandPoint

San Antonio Police Department, Texas: Intergraph (Hexagon/Denali) inPURSUIT Records Management System

San Jose Police Department, California: Versaterm Versadex Records Management System, version 7.3

Stockton Police Department, California: Tiburon LawRecords version 7.10

Tucson Police Department, Arizona: Intergraph (Hexagon) iLeads

If you have records on a database not listed here that you’d like to share with the MuckRock community, please email [email protected] .